The Body as a Mandala of the Universe

Diego Frigoli*

Ecobiopsychology is a new discipline that falls under the epistemology of complexity and sets out to relate the semiological codes of the infinite forms of the world and their particular languages (ecological aspect), with the analogous languages of man's body (biological aspect), and then to find the relationship between “universe” and “bios” in the psychological and cultural aspects of man himself, thanks to the images present in myths, in the history of religions, in dreams, and in the representations of the collective unconscious (psychological aspect). Ecobiopsychology stems from the most recent developments in systemic science which imposes a new way of looking at the world, man's body, and his psyche by considering them as a kind of hierarchy of matter and energy, structured in terms of in-formation.

Drawing on the most recent developments in physics, cosmology, biology, and psychology, modern science emphasizes the need for a unified view that conceives the cosmos more as a living organism than as a dead physical reality; space and time as joined together by a dynamic relationship; matter and energy as interchangeable aspects of each other in a new field reality; the biosphere as a network of interconnected phenomena; and the individual and collective mind as an integral part of the web of life, itself an integral part of the universe.

In holistic terms, we have moved from macro-systems such as that represented by the cosmos, studied by cosmology, to the micro-systems of matter, studied by quantum physics, to emphasize how in both levels of physical reality we recognize the presence of an integrated system, where each particle interacts with everything that exists to compose a great Whole. It has been argued by several voices that there are in the universe instantaneous correlations between living organisms, as well as between the parts of an organism and its totality, to the point of thinking that humanity is facing more than a development of science to a new era, represented by the awareness of a synchronic world, open to a development of an unusual form of intelligence: the cosmic one (Biava P.M., Frigoli D., Laszlo E., 2014; Aczel A.D., 2004; Bohm D., 1980).

In the landscape of these frontier studies, Ecobiopsychology has been emerging from somatization studies conducted on patients with disparate illnesses, generally of medical expertise. With a thorough research program, it sought to find links between the pathology of an organ or apparatus with specific fantasies emerging from the unconscious about the diseased organ or apparatus.

Examination of these correlations revealed that in numerous pathologies could be traced not only fantasies from traumatic memories experienced in childhood (personal unconscious), but also true archetypal images, present in numerous cultures, myths or religious traditions. From these initial studies, Ecobiopsychology has developed its research by combining the Jungian approach on the collective unconscious and archetypes with more recent developments in evolutionary biology, with the aim of specifying and more systematically investigating the archetypal correlations between the phylogeny of the body and the mental images present in somatizations (Frigoli D., 2013; Frigoli D., 2016).

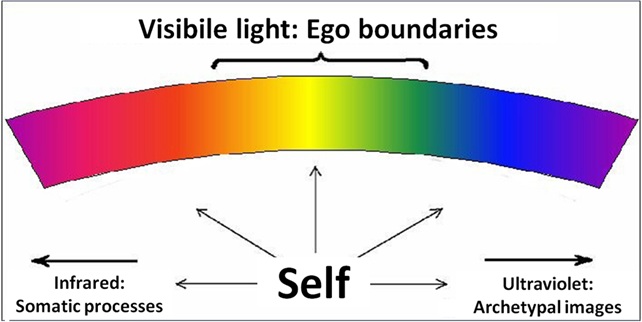

As clinical observations became more precise, the concept of archetype, studied by Jungian analytic psychology, took shape not only as an ordering factor of psychic images as it was intended, but also as a real structuring modality of the psychic and the bodily aspects. Taking up the model with which Jung had synthesized the relationship between archetype and individual reality, consisting of the figure in which the archetype of the luminous was represented, it was observed that the continuum of the archetypal phenomenon of light extended from infrared to ultraviolet rays, passing through the visible band.

The visible band, which oscillates between well-defined light frequencies, corresponds to the reality of the Ego complex, capable of grasping only a fragment of the archetype's energetic totipotentiality. The infrared band corresponds to instincts and phylogeny, and the ultraviolet band to the subtler aspects of the psyche and spirit, which ordinary consciousness does not grasp. In this classical Jungian approach, the archetype had been configured as an exclusive ordering factor of mental images with no relation to the body and its evolution, remaining almost a transcendent entity difficult to understand.

In the ecobiopsychological approach, which, as noted above, recovers the latest studies in evolutionary biology and quantum physics, the archetype has taken a central, we might say psychosomatic, view of both the instincts of the body and the mind and the development of images. In other words, at the infrared pole according to Ecobiopsychology, instinctual somatic processes are traced, represented by different physiological “functions” and anatomical structures depending on the level of the phylogenetic scale at which we wish to situate ourselves, while at the ultraviolet pole the archetypal images are presented amplified in their symbolism depending on their expressiveness concerning the world of the supersensible.

The ability to find the information coherence between the various levels of infrared and ultraviolet, will come to represent for the Ego complex (the band of the visible) a precise reading of the modus operandi of the archetype, which in the ecobiopsychological perspective will become not only an ordering factor of the psychic images, but a real “ens creationis” of the body and the evolution of the mind with its images.

In this way, the archetype will assume the role of the generator of the energy field of in-formation destined to create matter and psyche, body and mind, and their mutual relations, but also play a role analogous to the attractors present in the study of complex phenomena, in gathering into a unified field information of the body and mind. Let it not be thought that these conclusions are far-fetched, for today scientists skilled in cognitive linguistics do not hesitate to assert that the «mind is deeply embodied in the body and thought is mostly unconscious» (Lakoff G., Johnson M., 1999); with this statement they hint at how our conscious thought (in the ecobiopsychological model the “band of the visible”) depends for the most part on the activity of cognitive processes that operate at a level inaccessible to our ordinary consciousness, that is, at the level of our cells and organs (infrared band), where cognition and autopoiesis is located.

If the revolution brought about by evolutionary biology tells us that in every living organism--plant, animal, human--life and cognition are inseparably connected processes, to the extent that mind is inherent in matter at every level in which life manifests itself, it will follow that there must exist between mind and matter a constant in-formative coherence determined by archetypal activity. The conscious reading of this coherence, at all levels in which it can be found, will determine in the ordinary consciousness of the Ego its own orientation toward the direction of an awareness of the mode of functioning of the archetype.

In this perspective of ecobiopsychological study, the human body will no longer prospect itself as phenomenologically determined by only the subjective value (the Leib of phenomenologists) different for each human being, but also in the new role of “concretized” archetype, which through DNA condenses in each cell the time of phylogenetic evolution parallel to the evolution of “cognition”, present in cells, organs and apparatuses (primary consciousness) (Maturana H., Varela F.J., 1980).

This means that the human body, beyond its subjective value as an ontogenetic reality, summarizes within itself a phylogenetic reality, that of the universe that has been synthesized into the form “man”. Therefore, by studying man's body not only in its dimension of more or less altered functional balance or in its “libidinal” expression, as psychoanalysis wants, but also as a “formed form”, the result of an archetypal creation, the body will assume the role of a “cosmic mandala”.

Its infrared and ultraviolet aspects will represent the psychosomatic functions brought together in the higher plane of the Self, which, as a unifying symbol of their construction and functioning, will respond to the same laws upon which the universe is built. Thus, if the form and functioning of the body is a concrete manifestation of the archetype of order, of the psychosomatic Self, knowing the body and its functions in their dimension of coherence with the images will mean delving into knowledge of the mysteries of the archetype and thus of the world.

What tool does Ecobiopsychology use to study the body as a creation of the archetype? We know that nature is an “organism” governed by universally accepted laws, the same laws that are present in the depths of our psyche; only an approach that takes this correspondence into account can make the relationship that exists between these two domains less and less impenetrable. From Jungian analytical psychology, we know that the collective unconscious, unlike the personal unconscious, opens up to a larger, energetic and totalizing dimension, which provides the archetypal form, in itself “empty”, with a “fullness” of representations that will become sensitive to consciousness in the form of archetypal images, expressed as symbols.

Thus, the symbolic function is in man a place of “passage”, of union of contraries, because the symbol in etymological terms expresses the faculty of “holding together” the conscious “sense” (Sinn=sense) of the perception of objects, with the “raw material” of the image (Bild=image) emanating from the depths of the unconscious (Jung C.G., 1947-1954).

In its operational dynamics, the symbol is structured on the function of analogy (analogy = proportion), which on the level of communication theory has its roots in the protohistoric period of the evolution of human consciousness, where that “auroral” aspect of transition between the unconscious and the dawn of consciousness dominated. With the symbol therefore, the conscious psyche will be able to approach the totipotentiality of the collective unconscious without being overwhelmed by it, but at the same time, by making use of analogy and its a-causal approach in coordinating the symbolic images, tying them together in an almost mathematical “proportion” of connections, it will allow a confrontation with the invisible of the archetype, without losing its faculty of discrimination. Analogical “proportion” will thus be a practical way for the psyche to give meaning and order to the in-formative field of the collective unconscious, which not only involves the whole physicality of matter but also man himself, in his physical and mental dimensions.

Perfectly understanding, through analogy, the meaning of shapes, colors, and images of everything around us is a way to see the archetype everywhere, to open up to the totality of the world as an experience of meaningful correspondences, once designated as Unus Mundus. Indeed, analogy, by allowing ordinary thought to perceive the circularity of the webs of life, amplifies it disproportionately to the point of making it infinite, allowing one to concretely experience the dimension of the continuum of the Unus Mundus (Melandri E., 2004).

In this way, the transition of the individual psyche from an ordinary level of reading the world, to another level of consciousness, represented by the discovery of the correspondences proper to the Unus Mundus, may take place empirically in man. If identified, these correspondences will become “vital analogies”, because they will resonate the dynamisms of man's body and psyche, his holographic information that is, with that of the universe, thus causing the subjective psyche to empirically experience openness to the universality of the world.

This field shift involves for the individual psyche a profound transformation in the direction of awareness of the “subtle body”, defined as the unconscious aspect of the body's structure. The subtle body can be understood as the consciousness of the “cognition” of cells, organs and apparatuses in the human body, broadly speaking as the conscious aspect of the unconscious of matter.

In the field of psychotherapy, the ecobiopsychological practice will therefore designate an informational field placed far beyond that described by modern schools of psychology, because the therapist by always searching for the analogies present in the therapeutic relationship on all planes - biographical, dreamlike, imaginary, creative - will give the search for mentalization a poietic status (Gr. Poiesis = creation) at the center of which will be the experience of the archetype and its design. Thus, the ecobiopsychological field that will take shape in therapy will unfold as if the patient presents a kind of “cloud” of potentialities and existential possibilities, an expression of his Self, which in the confrontation with the therapist, through the involvement of the subtle bodies of the protagonists, will “collapse” in a specific direction, represented by the coordinated listening of all the images evoked in therapy, oriented towards the direction of the individuation process (Frigoli D., 2017).

The mandala: the memory of life

«The greatest and deepest emotion we can experience is the mystical feeling. In it is found the germ of all true science. He who is distant from this emotion, who can no longer be surprised by awe or lost in ecstasy is a dead man. Knowing that there is that which is impenetrable to us constitutes the deepest wisdom and the most radiant beauty that our dull faculties learn in an extremely primitive form from the most superficial aspects of any religion, cosmic religious experience is the most powerful and the oldest source of scientific research. My religion consists of a humble admiration for the boundless Higher Spirit, which reveals itself in every smallest detail perceived by our frail and weak spirit. This deeply emotional conviction I have of the presence of a higher rational power, manifested in our incomprehensible universe, forms my idea of God» (Albert Einstein).

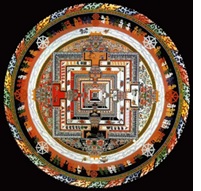

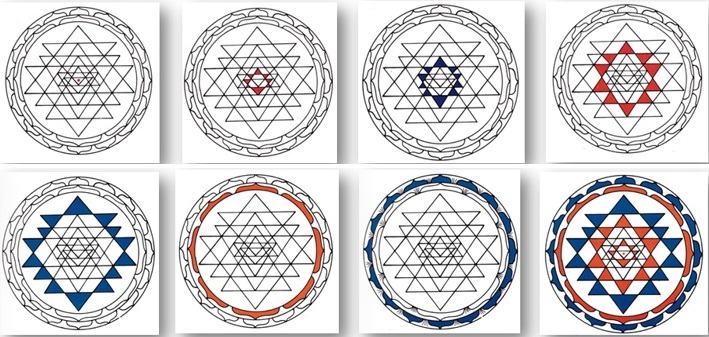

What does the word mandala mean? (Tucci G., 1974; Ajit Mookerjee, 1975). It is a Sanskrit word whose meaning responds to the image of the “circle” and indicates the psychograms used for meditation purposes among Hindu and Buddhist schools, especially within Tantrism. The mandala consists of very complex signs executed on cloth, paper, leather, wood or even simply traced on the ground-usually composed of one or more concentric circles enclosed by an outer belt, inside of which is a square, called a vim?na (palace, sacred city), equipped with four gates and divided into four triangles by the tracing of the two diagonals: inside each triangle and in the center of the entire mandala are five circles containing divine symbols and figures.

he outer belt of fire represents the bulwark against negative powers, while at the same time symbolizing metaphysical knowledge that burns away ignorance. Inside, the diamond belt evokes purity, stability, supreme consciousness and enlightenment. The fearful visions of cemeteries celebrate the death of all that is profane, and the belt of leaves or petals the occurrence of spiritual rebirth.

The four gates that open in the mandala's perimeter at the four cardinal points separate sacred and profane space and are manned by terrifying guardians who discourage the uninitiated from accessing them. In numerous depictions, the irate deities correspond to unconscious drives to be sublimated, while the gods in amplexus evoke the mystery of overcoming the painful subject-object duality in the supreme realization of Oneness, constituted by the ineffable smile of the Buddha as a symbol of the vacuity of the mind that has been able to annihilate its conditioning. In this structural scheme that leaves room for countless variations, each individual part has its own precise meaning and function within the framework of a complexity of symbols that, on the basis of a quinary division (the five elements, the five senses, the five Buddhas, the five tatvas or categories of Kashmiri sivaism), suggest analogies between the individual, his psyche and the universe. The mandala is thus an image of the universe in its archetypal principles, but also a support for meditation and a tool for reintegrating the psyche into the absolute. If mandalas, found in the Buddhist area, are iconographically enriched with figures, objects, environments and numerous details, in Tantric yoga the practice of concentration makes use of symbolic diagrams, articulated in geometric shapes called yantras[1].

Through the internalization of these figures, “animated” by specific mantras, the practitioner achieves a journey into the depths of being in search of the “center”. Thus mandalas, yantras, and mantras represent visual, and sound supports to facilitate the fixation of thought and mind, preventing it from floating on the choppy sea of the psyche. From symbol to symbol, levels of consciousness not definable by common speech are opened up to the practitioner, for through a process of evocation and assimilation of the cosmic energies, condensed in the force fields of the mandala and yantra, energized by the correct pronunciation of the mantra, it will be possible to gradually proceed to an understanding of the mystical Oneness (the Atman and Brahman), dispersed throughout the manifold.

On the psychological level, mandalas and yantras thus represent the unifying symbols that enable the subjective psyche to come together in the higher plane of the Self. They occur in more or less abstract form, because the symmetrical ordering of the parts and their relation to the center constitutes a kind of law that allows the mental images or the geometric structure of them to direct the “disorder” of the psyche toward that primordial order given by archetypal reality.

Buddhists say that mandalas are essentially mental, and that physical images serve only to construct the true mandala that is formed in the mind. Mandalas are consecrated on the floor of temples, building them with colored sands only for the period during which the religious service is held, at the end of which the mandala is simply destroyed, sweeping away the colored sand of which it is composed. This gesture signifies the impermanence of things and their rebirth, since in giving life there is not only the constructive but also the destructive force. The universal spread of the mandala, which has been present in all cultures from time immemorial, testifies to its archetypal origin as a search for the center of being, on the condition that one knows how to orient the mind to grasp the different dimensions of the reality of existence, represented by symmetry and the four cardinal points that define the ordinary space of the Ego and its conscious sensations.

If the human being, in other words, knew how to know “vitally” how to realize the transition symbolically represented by the square (representing earth and materiality) to the circle (representing the spirituality of heaven), he would know how to compose Spirit with Matter, the Transcendent with the Immanent, realizing, according to the alchemists, the rebis or androgyne, as a catalyst capable of resolving all irremediable dualism.

In psychotherapy, mandalas often occur in the dream life of patients, and while they do not have the degree of perfection and precision of oriental mandalas, they stand for the need for psychic self-regulation as an expression of the search for ultimate wholeness, which, however, given our limited human nature, will always be only relative (Jung C.G., 1936).

Their appearance - according to Jung - does not stand for a particularly high stage of development of the individual, but rather for the need for a reordering of psychic representations in situations where there is an abaissement du niveau mental or a momentary twilight of consciousness. These ordered representations should be read as a spontaneous form of healing that human nature automatically deploys to overcome conditions of psychic fragility.

Ecobiopsychology, to these classical approaches of analytical psychology, adds the idea that if we study each “form” of the living world not only in its biological but also in its symbolic prerogatives, we can access that continuum of the Unus Mundus built on the basis of its in-formative expression of the archetypal order. This idea is not foreign to Western and Eastern wisdom, and has been advocated since antiquity, representing the theoretical basis of numerous sapiential sciences such as astronomy, magic, psychology and medicine, and also influencing religion. In the Renaissance hermetic tradition, Frances Yates showed that the idea that the universe was «one world (Unus Mundus) endowed with the cosmos as a body, a cosmic soul (connected to the body by an all-pervasive spirit), and the divine spirit of the world: the nous. The body contains the species (genera) of all things, the cosmic soul their rationes seminales, the cosmic spirit their ideae» (Yates F.A., 1964).

The relationship between species, rationes seminales and ideae constituted a field of reciprocal correspondences that could be perceived through the study of this cosmic mandala, capable of enabling man's psyche to amplify the scope of his consciousness. Ecobiopsychology, by repurposing mandalic study not only to psychic images but also to the coherence these entertain with the human body, in fact extends to the body and its anatomo-physiology the role of a mandala connected to the universe in its relations with DNA and with the archetypal images present in the mind.

This approach thus opens the consciousness of the Ego to the experience of that circular field of in-formation constituted by the operation of the archetype. For example, it is now known that DNA, the molecule responsible for the maintenance and perpetuation of information concerning everything about an organism, consists of a skeleton of sugars to which four types of nitrogenous bases are bound - Adenine (A), Thymine (T), Guanine (G) and Cytosine (C) - which being the only variable part of the molecule, are those that by arranging themselves in different orders give the genetic information.

Also to be considered is the fact that DNA, before being translated into proteins, is transcribed into an RNA strand. In RNA, the nitrogenous base Thymine (T), is replaced by Uracyl (U), which has very similar chemical characteristics. It has been shown that an amino acid is not encoded by a single nitrogenous base, nor by a copy, but by a triplet (called a codon). So, combinations of three nitrogenous bases encode an amino acid: thus, there are 64 (43) possible combinations.

This number is central to DNA biology. Let us now examine the I-King. The I-King is a very ancient divinatory text whose origin is lost in the mists of time and was commented on by Jung in his study of synchronicity as the basis of the holistic view of life. In the I-King the archetypal yang force is represented with a straight line, and yin with a broken line; all possible combinations of three lines make up the eight basic trigrams, while with six lines there are 64 hexagrams (or kua) for each of which a single chapter of the I-King is reserved.

In the hexagrams of the I-King one can find the structure of the universe, the cosmogonic principles and those of the coming into being, becoming and ceasing of all things. Comparing DNA with the I-King, it is remarkable to observe how the 64 combinations found in the Book of Changes correlate precisely with the 64 possible combinations of the nitrogenous base triplets that make up the genetic code of DNA.

In practice, just as the DNA pattern constitutes the basic information structure of the biological and organic dimensions of a being, so the I-King pattern describes the basic structure of the psychic and spiritual dimensions of the individual and the universe (Katya W., 1994). In pointing out these similarities, Ecobiopsychology does not want to make a suggestive and seductive conceptual operation, as much as to emphasize how the idea of number and its combinations is present at the basis of our cognitive processes of the Ego complex when they open up to the applied dimension in the direction of the archetypal Self; and on the biological level, in pointing out that number itself describes the evolution of inheritance extended beyond the time of the Ego.

In this field of study linking the Unus Mundus, the Bios and the Logos as subsets arranged in a network, and linked to each other by a criterion of vital proportion (analogy) capable of making their relationship coherent, great possibilities are to be glimpsed, for it involves carrying out research that addresses the study of how the specific “forms” of nature are linked with the archetype, and are found represented in the mental constructions of archetypal images.

Let us now examine in the light of ecobiopsychological epistemology three archetypal images derived from distinct knowledges: Taoist religion, Egyptian religion, and alchemy.

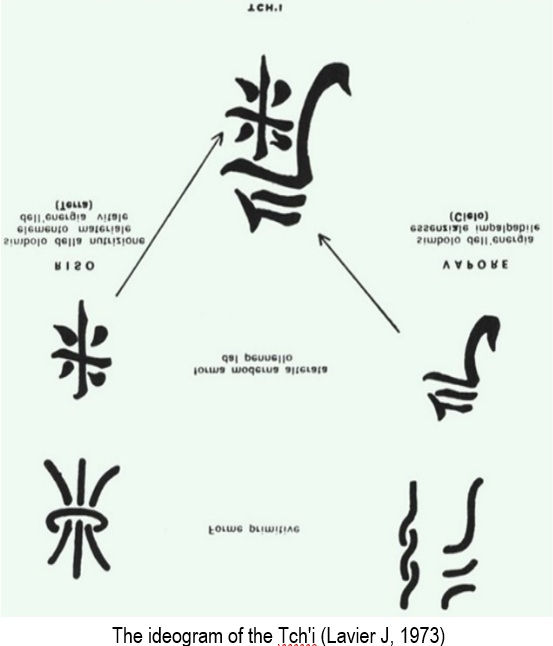

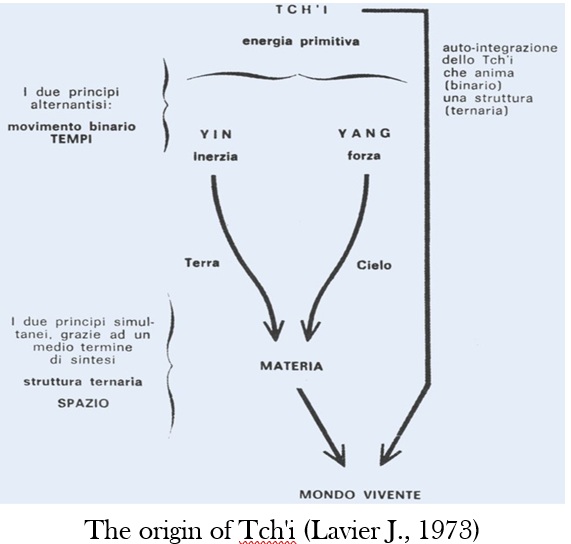

Tch’i energy

In the Taoist tradition, the cosmic energy Tch'i (Lavier J., 1967) was the basis of all phenomenal manifestation. Through its condensation, visible things were formed; through its rarefaction, a transformative motion was generated that led it to condense again on another plane, generating new forms. The ideogram of Tch'i energy is composed of two distinct elements. One is immaterial and “heavenly”, the other is material and “earthly.” One is formally represented by steam, the other by boiling rice cereal. Tch'i flows through the universe as a river of energy and into man's body through special channels called meridians, to which acupuncture was applied as a therapeutic modality to balance the defects or excesses of energy that cause disease. If, however, we delve deeper into the stage of the rice and steam pictograms and refer it by analogical translation to man and his psychophysical existence, we observe that the rice cereal arises from the earth when it is well nourished by water, and thus corresponds to man's well-balanced body on the alimentary and emotional levels, while steam presupposes heating intended to transform water into a volatile substance, air.

In the Taoist tradition, the cosmic energy Tch'i (Lavier J., 1967) was the basis of all phenomenal manifestation. Through its condensation, visible things were formed; through its rarefaction, a transformative motion was generated that led it to condense again on another plane, generating new forms. The ideogram of Tch'i energy is composed of two distinct elements. One is immaterial and “heavenly”, the other is material and “earthly.” One is formally represented by steam, the other by boiling rice cereal. Tch'i flows through the universe as a river of energy and into man's body through special channels called meridians, to which acupuncture was applied as a therapeutic modality to balance the defects or excesses of energy that cause disease. If, however, we delve deeper into the stage of the rice and steam pictograms and refer it by analogical translation to man and his psychophysical existence, we observe that the rice cereal arises from the earth when it is well nourished by water, and thus corresponds to man's well-balanced body on the alimentary and emotional levels, while steam presupposes heating intended to transform water into a volatile substance, air.

On the symbolic level in man, “warming up” corresponds to his capacity for creative excitement and design of emotional forces, which make him move from a static and generic condition, the same for all human beings, as an expression of his earthly identity, to an individual condition, different for each person, dictated by the personal capacity to “ignite” his libido to achieve transcendence (water turning into air) (Frigoli D., 2018).

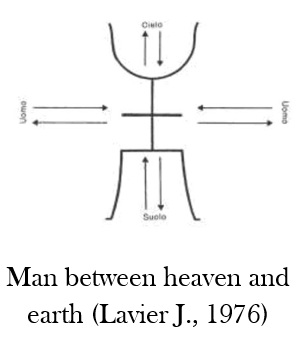

Thus, in the Taoist view, man, as an intermediary between heaven and earth, is not only a physical man, made of muscles, bones and blood, but in his meridians flows the cosmic energy Tch'i, that dynamic energy that pervades and regulates everything that exists in the universe, and that expresses itself through the activity of two opposite and complementary forces: the Yin and the Yang. Modernly, Tch'i energy could be understood as the biophotonic in-formation of the quantum energy that pervades the universe and consequently man (Esfeld M., 2018). As an intermediary between “heaven and earth”, man in his own constitution reflects this analogical correspondence between high and low, obeying the same archetype that created the world and himself.Today physicists call this archetype as Quantum Void Field or Akashic Field, consisting of a subtle sea of waves of energy from which all things arise: atoms and galaxies, stars and planets, living beings and their consciousness (Laszlo E., 2007).

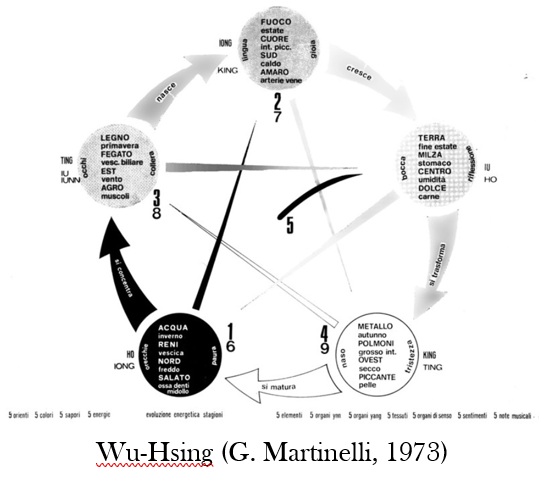

If man is a small universe, a microcosm where his organs and functions have close analogy with the phenomena of the universe, and if human existence is the product of the interactions of the energies of the archetypes of Heaven and Earth mediated by the in-formations of Tch'i energy, through the rule of Wu-Hsing, translated as “Five Elements”, “Five Powers”, the mutually corresponding yin-yang dynamic principles will find their concrete expressiveness in man's body, his psyche and the network of relations with the universe and its phenomenology.

The Wu-Hsing, a text called the Great Norm from the 4th century B.C., reports in full that man is regarded as a “materialization” of the archetypal Cosmic Self, which manifests itself both on the physical plane of organs and viscera and on the plane of psychic life, to the extent that there is always a two-way correspondence between the psychic world and the reality of the body. Just as the emotions have their specific correlate in the organs and viscera of the body, so the organs of the body possess their own specific psychic “reflection”, so much so that it becomes possible to modify the emotional world through a change in the bodily energies. Alongside this psychosomatic correspondence, there is a similar correspondence with Nature, which allows the anatomo-physiological structure of man's body to find itself in the same phenomena of the natural world through subtle, real and symbolic correlations, which dynamically open it to information from the universe.

It is not the case here to discuss in depth and empirically how the Wu-Hsing scheme works, but suffice it here to mention that it has such a universal scope that it binds every sphere of the macrocosm of the universe to the microcosm of man, in a complex scheme, where depending on the symbolism and analogical networks exercised by the hermeneutic it becomes concretely possible to observe the modus operandi of the archetype.

If each organ of the human body possesses specific particular phantasies within itself, can the human body understood as the totality of its own phylogenetic and ontogenetic history then be understood as the physical and material aspect of the archetypal Self? Here we are suddenly connected to Jung's archetypal conception, amplified, however, by the implication of the importance given to matter as a complementary expression to the psyche. This integration of biological and physical data with data related to the life of the imaginary is meant to intersect the history of biological evolution with the analogous history of the collective consciousness, which has fantasized about the body, its organs, and matter itself, resorting to metaphors and symbols deposited in the cultural heritage of all humanity. From this integration between the history of biological evolution and the history of collective consciousness, it will be possible to study the mode of functioning of the archetypes that Jung had explored in their function of ordering psychic images, forgetting for them their correlates with corporeality.As in the succession of psychic images, it will be possible to derive the most archaic ones, so they can be usefully related to the similar evolution of the corresponding organ in phylogeny (Frigoli D., 2018). For example, images of emotions defined as “cold”, “indifferent”, “hot”, “flaming”, “throbbing”, “fiery”, etc., refer to an unconscious expressiveness of the blood and its gradualness of emotional “temperature”, which can fluctuate on the phylogenetic plane from the blood circulation of fish, amphibians, and reptiles, all cold-blooded animals, to birds and mammals, warm-blooded. For each of these forms of evolution, the progressiveness of the nuances of their blood temperatures will have to be as consistent as possible with the descriptive metaphor of emotion. If, on the other hand, we speak of “undifferentiated”, “dull”, “indefinite”, etc., emotions with no connotations whatsoever, they will refer to a neutral “liquidity”, peculiar to the inner world of coelenterates, which live from a liquid life only, without a specific characterization that singles them out from their environment.Through the study of the similarities between the evolution of an organ or physical apparatus and the corresponding symbolic or metaphorical images describing them, it will be possible to construct a semantic network analogous to the biological evolutionary processes of phylogenetic evolution, thus enabling a kind of interpretive grid between the parallelism of biological evolution and the symbolic metaphorical images indicating the corresponding level of organic evolution. The images that will emerge at the psychic level will thus express their origin, anchored in the bodily forces of instincts and their history, which binds us to the inextricable web of life and its becoming. The immediate consequence of this intuitive approach to understanding the modes of archetypal creation of the face of the world, nature and its consistent connections with the anima mundi, may become the possibility on the part of man's psyche to remove the veil from the modus operandi of the archetype.

If each organ of the human body possesses specific particular phantasies within itself, can the human body understood as the totality of its own phylogenetic and ontogenetic history then be understood as the physical and material aspect of the archetypal Self? Here we are suddenly connected to Jung's archetypal conception, amplified, however, by the implication of the importance given to matter as a complementary expression to the psyche. This integration of biological and physical data with data related to the life of the imaginary is meant to intersect the history of biological evolution with the analogous history of the collective consciousness, which has fantasized about the body, its organs, and matter itself, resorting to metaphors and symbols deposited in the cultural heritage of all humanity. From this integration between the history of biological evolution and the history of collective consciousness, it will be possible to study the mode of functioning of the archetypes that Jung had explored in their function of ordering psychic images, forgetting for them their correlates with corporeality.As in the succession of psychic images, it will be possible to derive the most archaic ones, so they can be usefully related to the similar evolution of the corresponding organ in phylogeny (Frigoli D., 2018). For example, images of emotions defined as “cold”, “indifferent”, “hot”, “flaming”, “throbbing”, “fiery”, etc., refer to an unconscious expressiveness of the blood and its gradualness of emotional “temperature”, which can fluctuate on the phylogenetic plane from the blood circulation of fish, amphibians, and reptiles, all cold-blooded animals, to birds and mammals, warm-blooded. For each of these forms of evolution, the progressiveness of the nuances of their blood temperatures will have to be as consistent as possible with the descriptive metaphor of emotion. If, on the other hand, we speak of “undifferentiated”, “dull”, “indefinite”, etc., emotions with no connotations whatsoever, they will refer to a neutral “liquidity”, peculiar to the inner world of coelenterates, which live from a liquid life only, without a specific characterization that singles them out from their environment.Through the study of the similarities between the evolution of an organ or physical apparatus and the corresponding symbolic or metaphorical images describing them, it will be possible to construct a semantic network analogous to the biological evolutionary processes of phylogenetic evolution, thus enabling a kind of interpretive grid between the parallelism of biological evolution and the symbolic metaphorical images indicating the corresponding level of organic evolution. The images that will emerge at the psychic level will thus express their origin, anchored in the bodily forces of instincts and their history, which binds us to the inextricable web of life and its becoming. The immediate consequence of this intuitive approach to understanding the modes of archetypal creation of the face of the world, nature and its consistent connections with the anima mundi, may become the possibility on the part of man's psyche to remove the veil from the modus operandi of the archetype.

The god Ptah

In the preceding pages it was pointed out that, according to Ecobiopsychology, the archetype possesses a simultaneous psychic and somatic dimension, just as the Ego complex in organizing psychic life and its mental representations cannot be separated from the simultaneity of the corresponding bodily emotions.

In the preceding pages it was pointed out that, according to Ecobiopsychology, the archetype possesses a simultaneous psychic and somatic dimension, just as the Ego complex in organizing psychic life and its mental representations cannot be separated from the simultaneity of the corresponding bodily emotions.

In archetypal images, too, a “materiality” can be traced parallel to their psychic value, for they arise from our bodily emotions, from those primary aspects that nascent psychism (cognition) projects onto the matter of the world, carving out “figures” that are the psychic representatives of instincts. In this sense, the bodily instincts and rêveries of the psyche as a whole constitute that intangible fabric of more or less vast cohesion depending on the Ego's awareness of its “subtle body” as an expression of the matter-psyche continuum of the universe.

Let us now examine the religious image of the god Ptah found in the Egyptian tradition (De Rachewiltz B., 1983). First, it must be premised that in making contact with the religious morphology of Ancient Egypt, one can almost be stunned both by the many deities in its Pantheon and by the complex and varied structure of its theological systems. The Nilotic civilization was dominated by a “death complex” that had been built up through the representation of strange, anthropomorphic, zoocephalic deities moved by a phantasmagorical thanatological vision, where the dominant theme was the conquest of immortality. The conquest of a self-conscious immortality, not subject to the cyclical laws of becoming or the chains of animic transmigration, and the incorruptibility not only of spiritual principles but also of the physical body itself, were the fundamental goals toward which the joint efforts of religion and magic converged, amalgamated into an inseparable pair.

In order to understand the hidden meaning of zooanthropomorphic deities, it is necessary to refer to a particular process of “psychic vision”, according to which zooanthropomorphic deities are the representation of precise archetypal functions manifested within the living world (De Rachewiltz B., 1961).

The metaphysics of Nilotic thought did not rest on abstract matters but referred to knowledge of archetypal causes and soul functions operationalized in ritual practices. Their vision was monotheistic theocratic, and the conspicuous polytheism of their theology actually corresponded to the need to express only the “functions” of the divine, called neter, to signify the multiplicity of forces that enable life at whatever level it manifests itself.

The word neter, designating “God” in the Egyptian language, would be derived from a Ter root representing the annual flowering of the palm tree, and by extension the regular rebirth of plants. For the primitive Egyptian God would be a being who, instead of growing and dying like a man or animal, remains perpetually in the same state by periodic reintegration of all lost substance.

Neter is thus the Eternal or rather the eternally Self, the one who never dies. To understand the meaning of the neters, one must consider them in the very environment that represents their field of action that is, Nature. From Nature with its laws, which manifest becoming through all its transformations, the Egyptian priest was able to trace the complexity of the supersensible functions of the human soul through the minute examination of their analogical amplifications.

For example, to emphasize a walking man, a man with moving legs was depicted in hieroglyphics. But if the movement referred to the growth of vegetation, the moving figure was colored green. When hieroglyphs represented deities, on the other hand, they were much more complex to decipher, because in their iconography they expressed multiple levels of information, bringing together the plane of nature, with that of man and his spiritual reality.

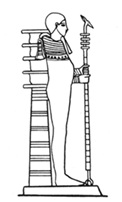

The god Ptah, for example, was considered in Memphis to be the oldest of the gods. He was considered by some sources to be the sole creator of the entire universe and was also sometimes believed to be a personification of “primordial matter” (ta-tenen). He was depicted mummiform, with a leather or metal cap on his head, and with his hands sticking out of the bandages he held upright a scepter called ouas.

Since in Egyptian iconography every detail of the Nether expressed an archetypal quality, it cannot escape notice that the ouas scepter is composed at the top of a series of overlapping disks, called djed, and above these of a stylized part of the elongated snout of an animal with large ears, which scholars have equated with the donkey and the hare. Because the ouas at the base, toward the foot of the Nether, is split in two, Egyptologists have traced it back to a tree branch cut at the point of bifurcation of the branches. Given that the point of bifurcation of a branch testifies to the force of growth that pervades it and that the head of the donkey or hare expresses the force of sexual instinct, the whole scepter ouas stands for a property of the god Ptah, that of the marvelous act of creation, which by generating determines the opposites of good and evil, represented by the bifurcation of the base of the scepter.

From the original duality (the base of the scepter), therefore, it was possible to reach Oneness (the scepter ouas) that confers firmness to life (djed as a symbol of stability), on the condition of realizing the consciousness of the fertilizing forces (donkey head or hare), expressed by the hands that consciously grasp the very force of the fertility of life.

The god Ptah, therefore, on the archetypal infrared plane, represented the nature of stability because with his back he was leaning on the djed column, but also stood for the continuous force of the creativity of life because with his two hands he held the ouas scepter. The head then was covered with a leather or metal cap to express that continuous generation occurred through a conscious consciousness, no longer subject to unconscious emotions. On the human plane, the god Ptah represented in the body the spinal column, both as a supporting and stable function and as a supporting function of the skullcap, the seat of conscious creativity of the brain and the generative apparatus of the psyche. In the psyche then, the god Ptah represented the conscious will power that gives stability and creativity to the mental life, and in the ultraviolet dimension of the spirit, the force of faith that makes the path of the soul stable and active (Schwaller de Lubicz R.A., 1949).

Each deity, therefore, when carved in stone, serves to provide an eternal awareness of the archetypal forces hidden in nature and the soul. The particular iconography of deities therefore conceals secret things, not so much for the sake of secrecy, but because in their symbolism are hidden the insights of the laws of the energy of the body and mind that cannot be transmitted and communicated directly but only through symbol, so that their awareness can enable the awakening of consciousness to soul knowledge.

In fact, the ancient priestly class of the Egyptian world carefully concealed through the Isidean and Osiris “mysteries” the “concrete” way of providing laymen with the “passport to the Beyond,” a sacred subject reserved only for the initiates and Pharaoh. The esoteric tradition taught in the “Book of the Dead”, how the image of the Solar Boat presupposed for the initiate's consciousness a special awareness of the significance of the Moon and Sun in their indispensable coniunctio, so that one could achieve that spiritual unio that allowed one to overcome the “laws” of nature to come closer to achieving immortality of consciousness. For the Egyptians, the daytime journey of the Solar Boat under the celestial vault was visible, but what happened during the night, where the Boat sailed in a reverse direction in a region that was neither celestial nor terrestrial? This night crossing was difficult and dangerous, but the deceased after death or the initiate in life should have endeavored to accomplish it, not by their own means but by boarding the Boat of Râ. For the Egyptians, only the knowledge of the “Twelve Gates” could have provided a symbolic description of the difficulties of the soul's journey towards its integration into the infinite.

No civilization of the past has ever revealed the grand global effect of the essential enigma of the mystery of death, exclusive, absolutely maintained knowledge that only the “dazzling” of a consciousness close to awakening would know.

The Ouroboros

Let us now address, through Ecobiopsychology hermeneutics, the study of the Ouroboros symbol. The oldest representation of the Ouroboros is found in a vase discovered at Nippur in Mesopotamia, the seat of the cult of the Sumerian god Enlil, lord of the Universe. As a celestial serpent Macrobius (3rd-4th century CE) attributes its origin to the Egyptians and Phoenicians. As a circular serpent biting its tail by the Egyptians it is said that: Draco interfecit se ipsum, maritat se ipsum, impregnat se ipsum (kills himself, marries himself, fertilizes himself), indicating a secret process of self-regeneration of Ego consciousness in the direction of self-discovery. Like Aion and Leviathan, it corresponds to En to Pan, a symbol of the eternal cyclical nature of all things. This symbol is also found in the Revelation of John, and in Gnosis among the Ophites. By the latter it is understood as primary celestial water that corresponds to the outermost circle of the world of creation that separates the latter from the divine world of Love and Light. Confirming its archetypal origin, this image is also found in the sand paintings of the American Indians, the Navajos, and in alchemical texts. In the West, the oldest description of this symbol is found in the Hieroglyphica, the only systematic treatment of Egyptian hieroglyphs by Orapollo (450-490 A.D.), who headed one of the last pagan schools, that of Menouthis, near Alexandria. This text arrived in Europe in 1422, thanks to a manuscript brought to Florence from the island of Andros by the Florentine traveler Cristoforo Buondelmonte.

A work written in Greek, the Hieroglyphica saw the light of day in the pagan circles of fifth-century AD Egypt, by which time Egyptian civilization had disappeared and with it the understanding of its secret system of writing. Characteristic of the text is to give a symbolic interpretation to signs whose meaning had been shrouded in mystery for centuries. According to the author, the Ouroboros is one of the ways in which the Egyptians represented the Sun and Moon; they are in fact eternal elements.

«When they wanted to represent eternity differently, however, they depicted a snake with its tail hidden under the rest of its body, called uraeus in Egyptian and basilisk in Greek». It, according to Orapollo, is a symbol related to the cycle of the seasons and the stars. In fact, to signify the World the Egyptians »place a serpent devouring its tail, and the various scales of it, represent the Stars of the World. Certainly, this animal is very grave in size, yea like the Earth, and still slippery, resembling water: and it mutates every year together with the oldness of the skin. For which thing time making each year change in the World becomes young». In fact, in the “Book of the Dead” it is said «I am Sata, (the primordial serpent who surrounds the world protecting it from cosmic enemies) elongated by the years, I die and am reborn every day. I am Sata who dwells in the remotest regions of the world» (Roob A., 1997).

From ancient Egypt, thanks to the Phoenicians, the symbol arrived in Greece and was imbued with other meanings, only to be picked up by imperial Rome, by Gnostic brotherhoods, and later in the alchemical and hermetic spheres, thanks to Neoplatonic reflections in the 1400s.

This serpent represents time perpetually reproducing itself, but also eternity and its infinite space, as it predates the birth of time and space: that is, it represents the symbol of the original principle as All or Nothingness, in which contraries are still indistinct.

On the plane of humanity, it corresponds to the primitive condition of the earthly paradise, and on the plane of the individual to its pre-birth condition, of which the Ego has no memory. It is the mythical epoch of consciousness in which the conception of humanity does not yet exist but only that of the divine, and it is also the time when the proto-consciousness of the embryonic ego is still absorbed by Great Mother Nature.

This Great Whole contains within itself every sketch of future consciousness, a womb of in-formation that also contains the progenitor forces of life joined together in an unbreakable embrace. From them the world is born, and peoples in the various myths celebrate this generation where the begetter procreates without partners and without duality.

In Egypt in Heliopolis, the figure of Atum is the one who manifested himself into all forms of the universe through an onanistic act, and in India Prajapati took to praying and fasting and, fertilizing himself, gave rise to his own offspring. This “sacred serpent” is thus representative of a creative cosmic energy that, through the perpetuation of the cycle of death and rebirth, represents the eternity and indestructibility of nature, that is, of the cycle of life that is renewed, in which nothing is created and nothing is destroyed; as a consequence of this immortality, Ouroboros corresponds to “infinity”, present in all forms of life.

Not surprisingly, it was taken up by Gnosticism as a symbol of the god Aion, a Gnostic expression of the totality of time, space and the primordial ocean that separated the higher realm of pneuma from the dark waters of the lower world (Roob A., 1997).

In the alchemical tradition, the Ouroboros is a palingenetic symbol (from the Greek palin=again, and genesis=creation), that is, that it is “born again”, which in the alchemical process stood for the cyclic succession of distillations and condensations necessary to purify and bring to perfection the “Raw Material”. During transmutation the Materia Prima divides into its constituent principles, which is why the alchemical Ouroboros is also often represented in the form of the two serpents chasing each other's tails. The upper one, winged, crowned and provided with legs, represents the Materia Prima in volatile form, the one below the fixed residue, and by their reunion into a single crowned (hence victorious) leg-bearing Ouroboros we obtain the philosopher's stone, the “great elixir” or “quintessence”. What do these enigmatic symbols mean, according to which the spirit of the world, the giver of life to all, must unite with our matter, the just virgin earth, so that through the fire that “opens” all things a unity of substance can be obtained that sums them both up? Why then is it then referred to in alchemy as Lapis philosophorum to indicate the “consolidation” of this psycho-spiritual process and not as “stone” to specify that “solidity” achieved by the alchemical process that penetrates all things? Ecobiopsychological hermeneutics, which aspires to trace the semeiological codes of the “exact” correspondences between macrocosm and microcosm, uses the tool of life analogies as an indispensable code for the psyche to access the understanding of archetypal processes hidden under the veil of images.

In the alchemical tradition, the Ouroboros is a palingenetic symbol (from the Greek palin=again, and genesis=creation), that is, that it is “born again”, which in the alchemical process stood for the cyclic succession of distillations and condensations necessary to purify and bring to perfection the “Raw Material”. During transmutation the Materia Prima divides into its constituent principles, which is why the alchemical Ouroboros is also often represented in the form of the two serpents chasing each other's tails. The upper one, winged, crowned and provided with legs, represents the Materia Prima in volatile form, the one below the fixed residue, and by their reunion into a single crowned (hence victorious) leg-bearing Ouroboros we obtain the philosopher's stone, the “great elixir” or “quintessence”. What do these enigmatic symbols mean, according to which the spirit of the world, the giver of life to all, must unite with our matter, the just virgin earth, so that through the fire that “opens” all things a unity of substance can be obtained that sums them both up? Why then is it then referred to in alchemy as Lapis philosophorum to indicate the “consolidation” of this psycho-spiritual process and not as “stone” to specify that “solidity” achieved by the alchemical process that penetrates all things? Ecobiopsychological hermeneutics, which aspires to trace the semeiological codes of the “exact” correspondences between macrocosm and microcosm, uses the tool of life analogies as an indispensable code for the psyche to access the understanding of archetypal processes hidden under the veil of images.

I recall that “vital analogy” means those “proportions” that consistently link together the objective manifestations of archetypal functions, which have manifested on the infrared and ultraviolet planes. The term Petra stands for the rock that is both strong and angular at the same time, so much so that figuratively it is said to “turn to stone” to express insensitivity to severe pain, or to be astonished by astonishment. Furthermore, “first stone” or “cornerstone” means the most important stone that ideally supports the whole construction. Thus, on a figurative level it expresses the idea of solidity, stability and secure support.

Lapis, on the other hand, retains in itself a curious meaning, well summarized by the word “lapillus,” meaning stone erupted by volcanoes during the explosive phase, mostly together with ashes. Implicit in it is the idea of fire, of origin from the depths of the earth, thus of emotions and feelings arising from the ancestrality of the body, which properly processed by the internal fire of the body itself, can take on the substance of “solidified” states of consciousness and made definitely manifest to the psyche. In modern terms this is a neg-entropic state of consciousness, no longer an expression of the chaos of the unconscious.

If we resume examining the symbol of the Ouroboros in the light of ecobiopsychological hermeneutics, as an expression of alchemical operative practices, we observe that on the macrocosmic plane, the Ouroboros is representative of the ecliptic, that is, the maximum circle of the celestial sphere described by the sun among the stars of the zodiac in its apparent annual motion around the earth. The circle of the ecliptic forms an angle of 23° at 27' with the circle of the celestial equator, an angle that is equal to the tilt of the terrestrial axis. The terrestrial axis in turn, always pointing toward the pole star allows the sun's rays to fall more or less perpendicularly on the earth depending on latitude, determining the flow of the seasons.

If in the macrocosm the Ouroboros corresponds to the ecliptic, on the anatomo-physiological plane of the microcosm-human, the Ouroboros corresponds to the great blood circulation, which starting from the heart with the aorta artery returns to it with the vena cava. The triangular shape of the heart represents the head of the serpent-dragon swallowing its tail.

But what do the four inner legs and three outer horns of the Ouroboros symbol represent in relation to the alchemical process? The four legs represent on the macrocosm plane the periods of the equinoxes and solstices, that is, the phase of the ecliptic in which the cosmic consciousness expressed by the sun nourishes the earth. On the astronomical plane, the equinox is that moment in the earth's revolution around the sun when the latter is at the zenith of the equator. This name comes from the Latin aequinoetium, meaning aequanox=night equals day.

The solstice is in astronomy the time when the sun reaches the point of maximum declination in its apparent motion along the ecliptic; this means that the summer solstice and winter solstice represent the longest and shortest day of the year, respectively. The word solstice comes from the Latin solstitium composed of sol=sun and sistere=stopping. The impression of the sun “stopping” is due to the fact that at solstices the change in declination is very slow in contrast to equinoxes where the change in declination is more significant. On the symbolic level therefore, the equinoxes and solstices represent the cosmic moments when the nourishing “light” of the Eternal Divine Mind (the Sun) illuminates the complex and dramatic life of earthly matter, bringing to it the right “warmth” and the right “light” in exact proportion to the opacity of the shadow of matter.

On the microcosmic-human level, the heart with its blood circulation represents, as noted above, the motion of the sun in the astronomical firmament, and just as the latter sends out its life-giving rays in a circular direction, so the heart sends out its “rays” (the arteries and veins) infusing life to all the limbs. The heart then, as the visible representative of divine fire and love, is a unitary organ, summing up in itself: the duality of arterial (sun) and venous (moon) circulation; the trinity expressed by its triangular shape, with the downward-pointing tip tilted 23° and 27' to the right like the earth's axis; the quaternity of the four chambers: the atria and ventricles. Thus, in its function the archetypal laws of Unity, Duality, Trinity and Quaternity are condensed, so much so that of the heart we can say that it symbolically represents the Triune God, operating in the Quaternity of matter.

It remains for us to examine what the four inner legs of the symbol represent in the complex architecture of the microcosm-man. They stand for the blood vessels of the circulation, respectively: of the stomach-milk, liver and pancreas, intestines and kidneys-bladder, organs all responsible for the transformation of food, essential for the growth of the body. Man in the body is an ens (entity) made up of the four elements, and, in relation to the macrocosmic world, an ens of the Spiritus Mundi; the latter gives man his carnal qualities, but also those supersensible qualities capable of enabling human nature to embrace the whole universe.

Therefore, from an alchemical perspective, the operative knowledge of the micro-macrocosmic chord intended for the “practice” of the Lapis quest, necessitates that during the solstices and equinoxes (inner legs of the macrocosm) there must be a special process of nourishing the body or even fasting (inner legs of the microcosm) in order for the supersensible faculties of consciousness to develop, which are well represented by the horns, wings or crown, symbolizing the blood vessels of the small circulation of the respiratory system and the circulation of the brain, responsible for the higher functions of life.

In summary, in examining the Ouroboros symbol, as in all alchemical symbols, Ecobiopsychology examines not only their meaning on the plane of the mind (ultraviolet) but also of the body (infrared), in order to find, in the coherence between image and corresponding somatic process, the possible trace of an alchemical “practice” intended to renew the “raw material” of consciousness in order to its value of “solidified perenniality” (Lapis).

In the symbol of the Ouroboros therefore:

1) The choice of the serpent stands for that living form that crawls adherent to the earth and changes its skin (mutates) over time, renewing itself completely. For the alchemical adept this process must take place for his consciousness.

2) The “open eye” of the serpent stands to denote that the whole alchemical process must be accomplished with consciousness, until a condition of “perpetual awakening” is achieved.

3) The iconography of the Ouroboros conceals the various psychophysical processes, which are well summarized by the symbol of Synesius (370-413 A.D.). He was this writer, philosopher, and alchemist, who with his image of the Ouroboros, red on the outside and green on the inside, with four inner legs and three outer horns wanted to specify well the alchemical path. What do these colors represent? Green is that of plant chlorophyll and red is that of animal blood. What relationship exists between chlorophyll and the hemoglobin of blood? Both of these pigments are identical in terms of molecular structure, differing only in that chlorophyll contains magnesium, which gives plants their typical green color, while hemoglobin contains iron, which colors blood red. These pigments serve: chlorophyll to plant life to transform light into chemical energy (photosynthesis) and synthesize useful molecules; hemoglobin to allow proper oxygenation of the various tissues of animal organs. On the symbolic level, chlorophyll and hemoglobin are the chemical mediators that unite the living structures of plants and animals (the metaphorical “earth”) with the respiratory gases, that is, the “subtle part” of Air. In humans, the “green” of plants and the “red” of the body's instinctual forces will summarize by imaginative synthesis the path of phylogenetic life that finds in the Nervous System its moment of evolutionary completion, passing first from the Vegetative Nervous System (so called because it controls vegetative functions, i.e. those functions that are generally beyond voluntary control and that correspond analogically to the “plant world”) and then to the Central Nervous System, which summarizes in itself the control of the emotions (emo-agere=acting on the blood) of animals and humans.

In this perspective of “infrared/ultraviolet” synthesis, according to Ecobiopsychology it is intended to emphasize the possibility of accessing with consciousness the imaginative vision that relates man to the Unus Mundus, through a conscious path albeit introverted by the psychosomatic libido, able to “vibrate” with one's psychosomatic unity on the affine cosmic frequencies, so that that integral consciousness represented by the psychosomatic Self can awaken.

*Diego Frigoli – Founder and promoter of the ecobiopsychological thinking, Psychiatrist, Psychotherapist and Director of the School of Specialization in Psychotherapy ANEB Institute. Innovator in the study of imagery with particular reference to the element of symbol in relation to its dynamics between individual and collective consciousness.

Translated by Raffaella Restelli – Human Sciences scholar, linguist and psychologist enrolled in the British Psychological Society with which she actively collaborates. Graduated in Modern Languages and Literatures at the Catholic University of Milan and in Psychology at the Newcastle University, UK. Ecobiopsychological counselor. Collaborator of ANEB Editorial Area as a translator.

Accedi all'area riservata

Accedi all'area riservata